When I was discussing the Greek economic crisis last night with my colleague Ameera David, she asked me who I blame for the mess we are in. I told her I blame the euro because the euro is a monetary union created for political reasons without political union. It is a failure and the Greek crisis shows us one reason why. But I have a catalogue of other reasons. So I have decided to write

them down and explain my thinking to you in greater detail.

Before I begin, let me say at the outset here that I reckon Europeans are tired of hearing the incessant Euroscepticism of the Anglo-American punderati. If you look back over the years, Americans and Brits have made it their duty to profess deep and meaningful scepticism about the euro and even the European Union and I appreciate that Europe grows weary of defending itself against these barbs. But the criticism is often valid and Europe should take the comments onboard in order to reform the eurozone’s institutions before it’s too late. I write this then as someone who wants to see the European Project succeed, not as someone who wants to tear it down.

Failure to create fiscal authority

I think now deceased British economist Wynne Godley got it right in 1992 when he wrote about “Maastricht and all that” when the structure for the euro was first formalized. Here are the crucial bits of what he wrote:

“Although I support the move towards political integration in Europe, I think that the Maastricht proposals as they stand are seriously defective, and also that public discussion of them has been curiously impoverished…The central idea of the Maastricht Treaty is that the EC countries should move towards an economic and monetary union, with a single currency managed by an independent central bank. But how is the rest of economic policy to be run? As the treaty proposes no new institutions other than a European bank, its sponsors must suppose that nothing more is needed. But this could only be correct if modern economies were self-adjusting systems that didn’t need any management at all.I am driven to the conclusion that such a view – that economies are self-righting organisms which never under any circumstances need management at all – did indeed determine the way in which the Maastricht Treaty was framed. It is a crude and extreme version of the view which for some time now has constituted Europe’s conventional wisdom (though not that of the US or Japan) that governments are unable, and therefore should not try, to achieve any of the traditional goals of economic policy, such as growth and full employment. All that can legitimately be done, according to this view, is to control the money supply and balance the budget……As Mr Tim Congdon has argued very cogently, the power to issue its own money, to make drafts on its own central bank, is the main thing which defines national independence. If a country gives up or loses this power, it acquires the status of a local authority or colony. Local authorities and regions obviously cannot devalue. But they also lose the power to finance deficits through money creation while other methods of raising finance are subject to central regulation. Nor can they change interest rates. As local authorities possess none of the instruments of macro-economic policy, their political choice is confined to relatively minor matters of emphasis – a bit more education here, a bit less infrastructure there…[…]…The incredible lacuna in the Maastricht programme is that, while it contains a blueprint for the establishment and modus operandi of an independent central bank, there is no blueprint whatever of the analogue, in Community terms, of a central government. Yet there would simply have to be a system of institutions which fulfils all those functions at a Community level which are at present exercised by the central governments of individual member countries.[…]…It should be frankly recognised that if the depression really were to take a serious turn for the worse – for instance, if the unemployment rate went back permanently to the 20-25 per cent characteristic of the Thirties – individual countries would sooner or later exercise their sovereign right to declare the entire movement towards integration a disaster and resort to exchange controls and protection – a siege economy if you will.”

Wynne Godley anticipated the crisis in Greece almost two decades before it began. This is remarkable. And the logic of his analysis is clear and prescient. Removing the ability of a national government to deal with a catastrophic economic break without replacing that ability at the supranational level creates an uncontrolled situation that will almost invariably lead to a country’s exodus from the eurozone. This represents the failure of the eurozone at its most basic level both in terms of policy and understanding of economic policy.

The humanitarian crisis in Greece because of a fiscal vacuum is the first and most fundamental way in which the euro has failed as a currency. Leaving aside the crushing unemployment, over 50% for youths in Greece, the concept that citizens in a rich, industrialized country are lacking basic medicine at the advent of the 21st century is shocking and shameful. That the Eurogroup now arguing over what to do in their eurozone don’t see this as a first priority shows you what is wrong in Europe right now.

But there are other failures

Currency weakness

I take the German view that a weak currency is no panacea for weak economic growth. What you want to see is an economy in which productivity growth is high and this leads to low inflation despite high wage growth and high economic growth, causing the currency to appreciate. The higher wages insulate the citizenry from the currency appreciation as it had done in post-War Japan and Germany as their currencies appreciated against the US Dollar.

And the Germans, supported this strategy for the euro. Before the euro was born, there was a lot of angst about allowing Italy or Spain to enter into the euro because it was believed that their fiscal policies generated high inflation, forcing them into a weak currency regime. The Germans wanted the stability and growth pact to limit fiscal deficits for that reason. It is not a cardinal sin to have a fiscal deficit. Rather, let’s remember the thinking at the time. It was that running a deficit in good times and bad causes an economy to overheat and for inflation to rise and the currency to weaken. That was a major reason why the stability and growth pact was instituted.

But of course, the euro is a weak currency – at least in German terms. And the evidence for that comes from multiple angles. When the Swiss were forced to abdicate on their defense of the 1.20 Swiss Franc to the euro level, the Swiss Franc went through the roof. And the thinking by the Swiss was that, though the immediate pain may be great, eventually the Swiss currency would depreciate as time went on. After all, Switzerland was taxing reserve deposits. But this is not what has happened. The Swiss Franc has remained strong i.e. the euro has remained weak over time, suggesting that the euro actually is a weak currency.

Another a priori piece of evidence that the euro is weak is that Germany has run consistent and rising current account surpluses throughout its history in the eurozone. Former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke called the Germans out on this in April, writing:

“However, in recent years China has been working to reduce its dependence on exports and its trade surplus has declined accordingly. The distinction of having the largest trade surplus, both in absolute terms and relative to GDP, is shifting to Germany. In 2014, Germany’s trade surplus was about $250 billion (in dollar terms), or almost 7 percent of the country’s GDP. That continues an upward trend that’s been going on at least since 2000 (see below).Why is Germany’s trade surplus so large? Undoubtedly, Germany makes good products that foreigners want to buy. For that reason, many point to the trade surplus as a sign of economic success. But other countries make good products without running such large surpluses. There are two more important reasons for Germany’s trade surplus.First, although the euro—the currency that Germany shares with 18 other countries—may (or may not) be at the right level for all 19 euro-zone countries as a group, it is too weak (given German wages and production costs) to be consistent with balanced German trade….Second, the German trade surplus is further increased by policies (tight fiscal policies, for example) that suppress the country’s domestic spending, including spending on imports.”

That’s it exactly. The Germans are running a weak currency regime and they are running a tight fiscal policy to boot. They have replaced a coherent thinking about deficits and full employment in an overheated economy leading to inflation with deficit fetishism while still benefitting from a weak currency. That is a beggar thy neighbour macro policy that keeps German domestic demand low, while relying on the kindness of strangers for growth via trade. And again, this is all because of the euro. If the Germans weren’t afraid of keeping government debt levels low and near the 60% Maastricht hurdle as I outlined yesterday, they wouldn’t be doing all of this.

Lack of intra-eurozone Harmonization

Remember that term ‘harmonization’? People used to talk about it all the time in the run-up to the euro’s creation. They talked about getting all of the euro’s national economies in tune in order to make the economic unit more ‘harmonious’. Sounds nice, doesn’t it? Well, this is another failure of the eurozone. The sovereign debt crisis tells you that. But again, look at pre-crisis current account balances and it tells you there was no harmonization. Here’s how I put it in 2010 using Spain as the example:

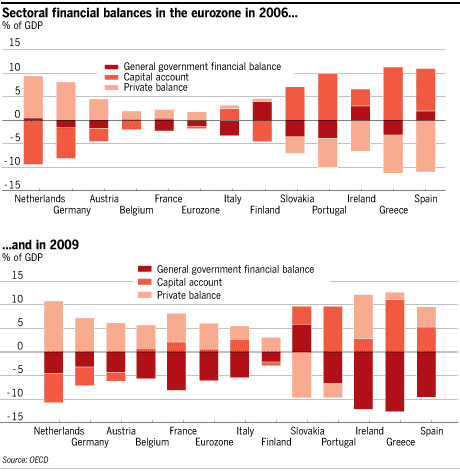

“The harmonisation never came to pass. Instead what we got was an unbalanced Euroland in which Germany and the Netherlands exported and Spain, Portugal and Greece imported, running up enormous current account imbalances in the process. Take a look at the capital account figures in the financial sector balances from this FT chart.”

“These imbalances are a direct result of a monetary policy that was geared to slow-growth core Europe. The result was an enormous property bubble in Spain and Ireland in particular. It’s not as if a robust regulatory environment could have overridden these forces either; the Banco de España, Spain’s central bank, is widely credited as having run one of the more solid regulatory regimes in Euroland. Yet, this did not stop a runaway property bubble from forming and imploding.”

All of this doesn’t really matter in a real currency union – one that has a political union and a central government. For example, no one knows or cares if British Columbia or Newfoundland are net creditors or net debtors because they are integrally tied into the Canadian political and economic unit. It doesn’t matter. In Europe it does matter because pre-crisis, the eurozone was one giant vendor financing scheme that enabled weaker domestic economies to gain strength via export to bubble economies. And that only works if the debtor can make good on its debts, which as we now know Greece cannot due to what I will call, the Godley rule which I pointed out at the outset: current account deficit countries in a monetary union without a central fiscal authority will face crisis when the economy turns down.

One size fits all monetary policy

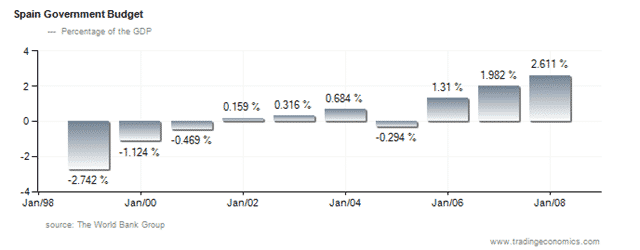

Crisis in Ireland and Spain is an example of the failure of a one-size fits all monetary policy.

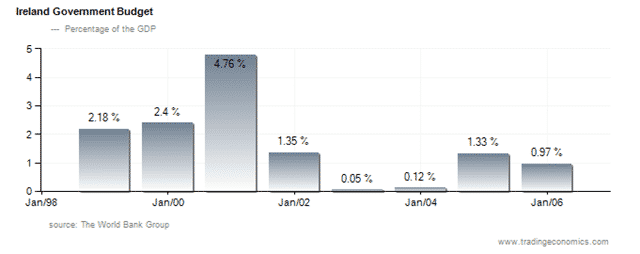

Notice how the government’s budget is in surplus throughout most of the 2000s. Here are Ireland’s government figures.

Surpluses for every single year to 2006. Why? Here’s David Beckworth from 2010:

the Eurozone is far from an optimal currency area–its member countries have different business cycles and insufficient economic shock absorbers in place–and the problems that this reality creates for the ECB in conducting monetary policy. One of the key problems is that the ECB is applying a-one-size-fits-all monetary policy to vastly different economies. For example, consider the case of Ireland and Germany. When the Euro was adopted in 1999 Ireland was growing close to 10% while Germany was growing around 3%. Should the ECB be responding to Ireland, Germany, or the average in setting its target interest rates? As the figure below shows, up through the end of the housing boom period Ireland was consistently growing faster than Germany. (Click on figure to enlarge.)Via Ralph Atkins we learn of Barclays Capital report that looks closely at this issue. Unsurprisingly, it finds the following:ECB interest rates have generally corresponded more to economic conditions in Germany – the eurozone’s biggest economy – than the eurozone as a whole.This means ECB monetary policy was well-suited for the low-growth German economy, but way too easy for the hot Irish economy.

The reality is that Spain and Ireland were hopelessly out of sync with the eurozone core and that ECB monetary policy was not well-geared to either country as a result. Without sufficient fiscal offsets or labour mobility, you get serious boom bust cycles as a result. And note, it is not at all clear that the boom bust cycles can’t repeat going forward. They can – and probably will.

Banking system fractured

Now clearly, if you are going to have repeated Boom-Bust cycles, you are going to get banking crises. And it is well-documented that Spain and Ireland received bailouts, not because of so-called fiscal profligacy. Rather, their banking system collapsed under the weight of an extreme boom-bust cycle. And in both cases, the government came to the aid of the banks, heaping debt onto its balance sheet, socializing losses onto taxpayers and putting the sovereign at risk for default. The Troika stepped in in each case but did not relieve either government of the contingent liabilities that crystallized when they rescued their banking systems. Going forward, however, we should expect the new bail-in rules to do the dirty work here. And this is expressly to prevent the kind of fiscal meltdown we saw in Ireland and Spain.

But the banking system in Europe is still fractured. There will still be national responsibilities to deal with. Look at the problems Austria is having with Hypo Alpe Aldria right now. To the degree, the Austrian banking system were to be impacted without a bail-in, the contingent liabilities would fall on the Austrian and regional governments. And to the degree bail-in rules apply, we would still see writedowns that reduce the net credit capacity of the Austrian banking system. This would negatively impact the economy, GDP and the Austrian government deficit.

While Austria’s banking system is weak, Italy is the focal point for me in this. Italy has had no growth for decades now. And it also has weak nominal GDP growth, such that despite a primary budget surplus, the Italian government debt to GDP is 140% and rising. Italy will be challenged at the next recession because the deficit will rise to perhaps the 150% or 160% of GDP level. That’s very close to Greek levels today. Would Italian banks be well capitalized? How many bad loans would mount due to recession? Would bail-ins feed a loss of tax revenue? All of this matters regarding contingent liabilities and private sector debt deflation if those contingent liabilities are not met. In the next recession in Italy, someone will have to increase the debt burden to replace the lost income due to souring debt. And if not, the lost income will result in a decline in GDP and tax revenue. Either way, government debt will go up substantially. Redenomination risk will mount if Greece has already left the eurozone.

Monetary financing failure

All of this won’t matter if Italy receives monetary financing from the ECB. But that is expressly forbidden under EU law. The issue of so-called monetary financing in the eurozone is problematic for a number of reasons.

First, in a real currency area where the monetary and fiscal authority are at the same level, there is always an explicit backstop from the monetary authority. After all, the monetary authority is simply the monetary agent assigned by the central government. The separation is artificial in order to promote sound fiscal operations and prevent inflation from building. Think of it this way: on the back of the British ten pound note it reads: “Bank of England. I promise to pay the bearer on demand the sum of ten pounds.” What does that even mean? Do you go to the Bank of England with your tenner and they pour out ten pounds in one pound coins. Frankly, it doesn’t mean anything. It’s fiat currency that is issued by government. It is a token to represent value based on government’s taxing power and ability to make its money legal tender for transactions and throughout the banking system. The government can print money at will if necessary – and cannot be involuntarily rendered insolvent in its own currency.

The point: in a modern currency area, for all intents and purposes, the central bank and the central government have a unified balance sheet, particularly in exigent times.

That’s not how it works in the euro area. The national governments are like states or territories without the ability to control their money. And as a result, in exigent times, they must cut back just like any other currency user, adding pro-cyclicality to the business cycle. Now, the US Federal Reserve engaged in quantitative easing during a period when the US federal government was running high deficits. One could call that “monetary financing”. But the Fed won’t engage in monetary financing of Puerto Rico because it is a Territory. And the same is true in Europe with the ECB and the individual eurozone states. The difference is that there are no Eurobonds in the eurozone and there is no democratically-elected Federal Government.

This is a flawed institutional arrangement which guarantees economic distress and crisis.

The resignations at ECB represent failure

And to make matters worse, there isn’t even common ground on how to conduct monetary policy in the eurozone. Two members of the ECB governing council have resigned in protest over the methods the ECB has chosen as it tried to deal with the sovereign debt crisis. Imagine this happening in the UK or in the US. It’s unthinkable. There may be differences of opinion between Fed Board governors but those differences are voiced at most in dissenting monetary policy committee voting, not in resignation. The resignations of Axel Weber and Juergen Stark from the ECCB are prima facie evidence of dysfunction regarding the conduct of monetary policy in Europe.

It is clear that the dysfunction emanates from the flawed institutional setup because of the Herculean task the ECB is thrust into taking on given the lack of a democratically-elected fiscal counterpart. Charles Wyplosz put it this way yesterday:

The deep reason for the Eurozone sovereign crisis is that the euro is a foreign currency for member countries. It also provides an example of how deeply politicized the ECB has become. No other central bank in the world tells its government what reforms it should conduct, nor how sharp should fiscal consolidating be. As a member of the Troika, the ECB was instructing Greece to carry out deeply redistributive policies, for which only elected politicians have a democratic mandate. In the end, it must accept the blame for poorly designed policies that have provoked a deep depression and its political consequences.

Conclusion

The eurozone needs a serious architectural overhaul. The sovereign debt crisis is a direct result of the eurozone’s flawed setup. And while Europe may be able to overcome this crisis in due course, Greece may end up being forced out of the eurozone or the EU entirely as a result. That would set a precedent for the violability of the euro as a currency unit, which would have negative consequences for redenomination risk contagion down the line.

But even after this crisis fades, more crises are sure to follow due to a lack of economic harmonization and a lack of political consensus on monetary policy at the most basic level. Boom-bust will continue, but with government debt much higher than before, the policy space will be even more limited in future. This is the recipe for political conflict and a disintegration of the eurozone.

The euro is a failure. And if Europe doesn’t recognize this and reform its institutions with great haste, the euro will join all of the other failed monetary unions in the dustbin of history.

TAGS: ECB, EURO, EUROPE, SOVEREIGN DEBT CRISIS

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου